Logic doesn’t apply to any of this.

In case you haven’t noticed, something happened over the weekend. A usual part of the American Super Bowl experience is some great new release, or trailer for the much anticipated movie of the coming year. But 2018 went one further – and even I, a man intolerant of sports discussion and up to date gossip – was well aware of it.

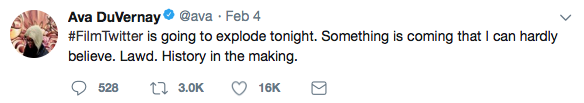

I first became aware after seeing that Ava DuVernay, award winning writer/director, notable for being the first black female director to be nominated for a Golden Globe and an Academy Award the following year, tweeted the following:

How exciting! It caught my eye, certainly, and a whole load of other film nerds on Twitter were twerping this way and that, wondering what it could mean. Is DuVarney up to direct a Star Wars film?! No. The truth, as some mysteriously managed to predict, was that there would be a teaser trailer for a brand new entry into the Cloverfield series.

Pretty cool.

Oh, and the film is going live on Netflix immediately after the game.

Holy shit.

Sure enough, The Cloverfield Paradox (2018) appeared on Netflix internationally, immediately after the game. It was unprecedented. It felt like the world was shifting. It felt like history in the making. Quite rightly, a lot of people were praising not only this – but the huge diversity in the cast and crew – including Nigerian-born director Julius Onah, and Gugu Mbatha-Raw, a black female actor, in the lead role. In a year that has taken leaps and bounds for representation on and off the screen, this would prove to be just another example of Hollywood opening up to the world around it.

Bit of a shame that it was all a bit shit, then.

Opening in the near future, we are introduced to an Earth on the brink of disaster. A global energy crisis is in full swing, with blackouts becoming a regular occurrence. Amidst the daily grind of queueing for hours to fill up at the petrol station, Ava Hamilton (Gugu Mbatha-Raw) and her husband Michael (Roger Davies) discuss the future. Specifically, Ava’s future. She has been asked to go into space to join a mission that might change the face of the Earth forever. A chance to develop technology that would lead to infinite, renewable power for the entire planet.

Initially reluctant, Ava is persuaded to join the mission by Michael, and we skip ahead to Day 16 of the mission. High above the Earth, Cloverfield Station rotates in orbit. Crewed by a number of representatives of the world below, the Cloverfield is designed to facilitate the testing of a new particle accelerator technology. But nothing’s working. As we skip through the days as part of the intro montage, we see the crew grow in frustration.

It’s been two years before things start to slow down. Disturbed by something in her sleep, Ava gets up to call Michael back on Earth. This is where I began to worry.

You see, despite what you may think reading these blogs, I studied Creative Writing at university. I admit, I didn’t do it for particularly long – but whatever. The point is, on day one, in my very first slice of further education, I was taught two things. The first and foremost can be summed up with the phrase: Never tell what you can show.

With this in mind, Michael proceeds to tell us everything that is happening on Earth, how he’s feeling and what normal life is like now. It’s hanging by a thread, incidentally. Michael says this as he sits in his well-kept bedroom, revising an illness suffered by one of his patients – he’s a Doctor, incidentally. One who is clearly still in work. Ava counters by stating exactly how she and the crew are feeling and that there is only enough fuel for a further three firings. Michael conclude step conversation by monotoning that he believes in the project and misses Ava, and their mysteriously absent children.

UGH UGH UGH. Here’s a thought: Why not have Michael watching the news when Ava calls? Show us the threat of invasion by Russia. How about Ava is engaged with a fraught conversation with another crew member about how they’re running out of fuel when Michael calls?

These questions and many more were only the beginning. The scene sets the tone for the rest of the film, which not even the genuinely impressive cinematography and production design can counter. But, hey, I’m getting ahead of myself.

Later, we meet the rest of the Cloverfield’s complement. In overall command of the mission, we have Kiel (David Oyelowo), engineer Schmidt (Daniel Bruhl), Monk Acosta (John Ortiz), with technicians Mundy (Chris O’Dowd), Volkov (Aksel Hennie) and Tam (Zhang Ziyi). Each have their role on board the ship, and after over 600 days on board the station, it becomes clear tensions are beginning to rise. Particularly between Volkov and Schmidt, who Volkov accuses of delaying the work on board to deliberately benefit Germany on Earth. This. This is interesting.

Later, while the crew are preparing for another test fire of the particle accelerator, Acosta watches a news feed from Earth. Some guy who Wikipedia tells me is Mark Stambler (Donal Logue) is banging on in true conspiracy theorist style that the experiments taking place in Earth’s orbit are too risky, and might lead to, and I paraphrase here, “…tearing apart space time, smashing together multiple dimensions, shattering reality. Not just on the station – everywhere. Monsters, demons, beasts from the sea … And not just in the here and now. In the past. In the future. In multiple dimensions.”

WE GET IT.

It’s so on the nose, it’s painful. But sure enough, when the experiment appears to be working, something goes terribly wrong. The crew are thrown about while consoles explode and the accelerator chamber bursts into flames. When the crew eventually resolve the immediate problems, they discover that there is a far worse issue at hand.

Earth is missing.

The crew are definitely not in Kentucky any more.

Or Kansas, for that matter.

This is only the beginning. It quickly becomes clear that things are even worse. Not only have they lost Earth, but the Cloverfield Station has been thrown into a different dimension. Here, the ordinary rules do not apply. Soon, the crew are chasing mysterious voices coming from the walls, a bunch of worms go missing, a dude’s eye goes wonky and the ship’s architecture gets a bit peckish.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg. Just as Mark Stambler predicts, everything goes wrong. While the Cloverfield Station is Holly Hopping between dimensions, creatures are beginning to appear all over Earth. Mysterious explosions and large, shadowy forms begin to emerge in the smoke and haze around Michael – our Earthbound witness.

The Event Horizon (1997) influence is palpable, with no small amount of lip service done to the Alien series – particularly Prometheus (2012). As I’ve already mentioned, The Cloverfield Paradox does genuinely look great, with a handful of truly effective set pieces. Of particular note is the discovery of Jensen (Elizabeth Debicki) on board the ship, Michael’s sighting at the hospital, Tam coming over all cold and, notably, Mundy’s dearmament.

Which takes me neatly onto the film’s true golden star: Chris O’Dowd. Established as the film’s comic relief almost immediately, O’Dowd stands apart from the rest of the cast for simply being charismatic. His presence on screen is an absolute delight, and a welcome change of pace from virtually everything else we’re being forced to watch. I don’t want to spoil anything, but the trauma he goes through might just be one of the most ridiculous sequences I’ve seen in a while, and the pay off is equally great.

Generally, though, the film is worth watching as an exercise in patience. Each mystery the film takes its time to set up feels wasted, with a number of characters introduced… for some reason. I’m sure we’ll be seeing multiple theory videos and, later, let’s-give-it-a-second-chance discussions, but, frankly, it isn’t worth it. The story itself, while fairly unoriginal, works. But I feel like it would’ve worked better as a standalone film, much like Life (2017). The connection to Cloverfield feels weak and tacked on – having read up on the background, I’m not surprised to find that this was exactly the case.

Which brings me onto the second thing I learnt in that first lesson in Creative Writing. Writing is re-writing. Never be afraid of a second draft. This is a film that was begging for a do-over on the screenplay. I’m not sure if it’s giving the writers Oren Uziel and Doug Jung enough credit, or perhaps too much, to think that there was more potential in this story. It was just handled badly.

Like, really badly. I’m not sure this is quite the earth-shattering film Ava DuVernay had in mind.

Yours, A P Tyler

P.S.

[SPOILERS]

Question time.

What happened with that black goo?

How did Mark Stambler know what would happen? Did he read the script?

If Volkov noticed the worms that mysteriously appeared in his body, how was he unaware of a great big gyroscope thing in his stomach?

What the hell was going on with Volkov’s eye?

Why do all the world’s representatives speak to each other in English, but everyone has to speak Chinese for Tam?

What was the point of the child that Michael saved at the hospital?

Why was she so creepy?

Why did the film keep showing us Michael’s phone when we can’t read the messages without pausing?

Why is Jensen so sketchy?

Who told Mundy’s arm the plot?

Does water really freeze in a vacuum?

When the worms burst out of Volkov’s corpse, why does everyone start stamping on them?

Why do we care about Michael?

Why would being upside down ever be an issue on a space ship or station?

Why did Ava insist on going to Earth and giving up her life and her husband, when she could just send a message down? Like she actually does in the end?

Why did we never see the interesting stuff happening around Michael?

Did anyone on set realise how terrible the dialogue is?

Did Netflix launch this film with no warning so no critics could reveal the truth beforehand?

How much money is Netflix making with terrible to mediocre films being exploitively marketed to social media audiences?

Why did we need the scene at the petrol station? What did we learn from that?

Is Mark Stambler related to Howard Stambler?

Does this matter?

Why did the wall become suddenly magnetic at the end?

Whhhhhhhhyyyyyyyyyyyy?

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.