You know, I have this pressing urge at times to try and be current. To not labour the point and go over things that have already been discussed a thousand times. When considering writing film reviews in this day and age, you can imagine this comes up fairly often.

It’s a feeling I had last week when I finally got round to watching Mel Gibson’s truly wonderful Hacksaw Ridge (2017). I had already heard a thousand and one opinions on it and just didn’t have it in me to throw my own voice into the screaming ring, too.

Conscientious Objection

For the few of you who don’t know it, Hacksaw Ridge tells the true story of Virginia-born Desmond Doss enlisting in the US Army during the Second World War but, due to his religious beliefs, refused to hold a rifle or kill another. It was, after all, the worst sin to commit in the eyes of the Lord. Instead, he signed up to serve as a Combat Medic and, in his own worlds, try to put things back together while the world tears itself apart. When he is eventually deployed to the front line in the Pacific, he is met with anger and mistrust by his fellow comrades. As the story progresses, however, he reveals himself to be brave beyond all sense, his dedication saving scores of men, while all others withdraw from the massacre. His bravery extends even to the Japanese soldiers wounded on the field, who he treats and rescues as any other man, amidst the hell of war.

At the end of the film, the audience is treated to a sequence of documentary footage, showing Desmond – the real Desmond – was awarded the prestigious Medal Of Honour for his actions at Hacksaw Ridge – the first conscientious objector to do so. But for all his honours, he remained frustratingly modest about the whole thing – it was his God that guided him. It was God that deserved the medal.

As this film was directed by Mel Gibson, it was inevitable there would be some degree of religious undertones. After his actions, Desmond is treated as if he were the Second Coming, particularly in the words of his commanding officer:

“All I saw was a skinny kid. I didn’t know who you were. You’ve done more than any other man could’ve done in the service of his country. Now, I’ve never been more wrong about someone in my life, and I hope one day you can forgive me.”

The implication is that this man is beyond mere mortal men. Anybody can raise a rifle, but it takes someone truly special to succeed without lowering themselves to our level.

This thought lingered with me for days afterwards. In a world of black and white – good and evil – should a true hero be without sin? More to the point-

Should a true hero kill?

It’s a tough subject to cover in my partially inebriated, semi-awake state this evening, but allow me to continue. Quite literally since the dawn of man, heroes have been held aloft as icons of courage, strength and guile. Virtually every culture on the planet tells tales of mankind’s fight against God and nature, whether it is through song, written word, recitation or – flash forwarding to the present day – moving image, audio books or video games.

The most prevalent subject is that of Heracles (later Hercules), a Greco-Roman hero born of a human woman and a God with a somewhat uncomfortable passion for Furry dress up games involved swans. The stories taught to me at school revolved around the Twelve Labours – you know, cleaning out the stables, stealing Amazonian bras, going Golden apple bobbing, filling out paperwork for a correct permit (though I may be thinking of Asterix at this point), etc. etc.

Regardless, the stories taught to me told of a man so brave, so strong, so flawless, that he stood up against anything thrown at him without losing an ounce of integrity. What I wasn’t told, however, was the tale of Heracles butchering his children after having a few too many urns of wine one evening. What a role model!

The tradition for heroic characters to be butchers and slaughterers of men is rampant throughout early history, particularly those that fall under the Greco-Roman banner. King Leonidas of Sparta springs to mind, particularly after seeing 300. It is, after all, a visually appealing and easily accessible way to showcase a character as going above – and beyond – all others.

An important distinction, at this stage, is the difference between hero as I mean it, and protagonist. A protagonist is the central point for a story, they are the character we – the audience – are meant to empathise with the most. They are our door into the world in which they live, regardless of whether they are the good guys. A protagonist is not necessarily a hero. In fact, in most forms of media, the protagonist can – at best – be considered an anti-hero. That is, someone who acts as a hero but are themselves damaged and, most importantly of all, an actual character with depth – a simple solution to the rarely asked question, “Why are anti-heroes the most popular types of character?”

Now, the idea of a sinless hero in the modern sense quite possibly has its roots in the Christian Bible. The stories told of Jesus Christ show him off to be beyond comprehension, especially on his words of peace and brotherhood. These attitudes continued through the years, with reports of early Christians being martyred without complaint or resistance. I imagine this probably lasted right up until the flames reached the testicles, but then hindsight is 20/20.

That isn’t to say that Christianity is the true origin of this, but with the fanbase that it had, I struggle to think of anything with such a wide reach in history. Later, there was of course the pacifist protests movements across the world. From Gandhi to Martin Luther King Jr., from China’s Mohism to the modern peaceful protests in Tahrir Square that toppled a dictatorship, there’s nothing that will baffle a military force more than choosing not to fight.

History is full of tales of bravery in the face of incomprehensibly low odds that were resolved without the need for violence – for their actions, it’s hard not to stand amazed at what was achieved.

Choose Your Own Adventure

Interestingly, this idea seems to resonate the most in the world of video gaming. Consider the likes of roleplay games such as Thief, Deus Ex – to some degree, even Fallout. You are invited to a world in which you alone can choose your path. You may choose to kill your enemies, but you are also encouraged to merely knock your opponents unconscious using your tactical prowess. Each method of play have their own benefits, but will ultimately result in extremely different end results.

Your actions, whether you choose to butcher your way through the game or use your brain and charisma to manipulate the world around you, have an effect. I would also say nine times out of ten, you really don’t want to end up with the bad ending.

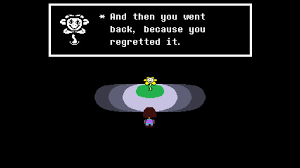

This is particularly evident in the hugely popular independent video game Undertale. As a child lost in the underworld, you are presented with the choice: Kill your enemies, or choose to spare them. In time, you are manipulated into feeling bad for the creatures and anyone who refuses to spare the poor little creatures simply does not have a heart and should be immediately assigned a government-funded therapist before it’s too late.

The path to pacifism in these types of games are not easy, indeed the choice to kill is often so easy it isn’t worth doing. For a real challenge, the player is asked to engage the characters in the world and find a better option than a polearm up the urethra.

This sort of thinking works wonders in the sort of extended story you would find in a video game or literature, which grants the audience space to invest themselves in an extended world. But in the realm of moving pictures, visual shorthand is still vital to setting up a story and concluding it in an hour and a half. Heroes must be seen to fight evil, even if they choose not to kill, you can guarantee they will still be seen punishing the baddies with some brutal martial arts or incredible feats of mental agility. Modern television is certainly closing the gap, particularly with the trend in extended visual dramas, but it is rare to find a hero that will choose the harder path – and walk it unarmed – in film and television as it is in other forms of media.

Does this mean, then, that a true hero should be without sin? That they should walk the longer path and succeed in conquering evil?

While it is true that a heroic figure should be one who has earned the trust and respect of those around them, I don’t think the matter of their virtue really counts. Heroism is defined as bravery, and what is bravery without a sense of loss? A hero must be the one to shoulder the burdens of the world, to understand what is at stake and to understand that a sacrifice – their sacrifice – may be necessary to achieve their goals.

To put this in perspective, a hero that inspires others through acts of pacifism does so knowing that they are at the greatest risk. The real life tale of Antoinette Tuff, who in 2013, talked a potential gunman down in Decatur, Georgia stands out here. As does the famous image of a single protestor halting a Chinese tank column in Tiananmen Square. So too do the soldiers throughout history who have saved their comrades, not with a bullet, but with their body.

A hero can be any of us, at any time. They do not have to be a murderer, but they must possess one thing above all others: Courage.

Yours, A P Tyler